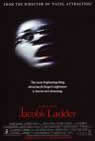

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Jacob's Ladder (1990) Film Review

The fat man sits in the corner, away from the pool players, opposite Jacob. He is sweating. His eyes dart across the room, from face to face.

"They're coming after me. They're coming out of the walls," he says. "I'm so scared, I can't go anywhere."

Jacob knows. He understands. For a moment, they feel safe.

Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins) works for the US Mail. He's a college graduate, an intelligent man, who left his wife and children to live in slum housing with Jezzie (Elizabeth Pena), a neurotic file clerk "with great thighs", because, she likes to remind him, "You sold your soul, remember? For a good lay." He laughs. He can't remember.

After Vietnam, "I didn't want to think any more." He has flashes of that terrible moment when it seemed the whole world exploded and his platoon was fighting for its survival and he lay wounded on wet, green, glittering jungle moss, waiting for the medics to haul him out, up into the sky, into the body of a purring bird.

The city is ragged. Everywhere there is filth, debris. Homeless hobos fester the subway trains. A deranged woman stares into the void. He speaks to her; she can't answer. He is watched by ghosts.

He tells Jezzie, "New York is filled with creatures. They're like demons." She has no patience with other people's problems. She wants attention, love, wild times. "I'm tired of men flipping out on me," she snaps. Jacob isn't flipping out; he's losing his mind.

Paranoia affects his ability to resist. He remembers his wife and children, especially the beautiful Gabe (Macaulay Culkin), who was killed, aged eight, by a car. He can't forget, like memories are his breath. He goes to the hospital to see his doctor, but his name is not on the register and his doctor's gone. It's a conspiracy, he thinks.

Jacob is not an hysterical man. He recognises the isolation of his fears. If he sees strange things that indicate an evil force, why should anyone else believe them? Either he is ill, or being made to think that he is ill. He begins to fight back, investigate the mystery of what is happening to him, but circumstances keep switching, as if his brain won't engage and real life, past life, dream life interchange.

The confusion is caused by an exterior power. Not inside his head. Or so he believes. Then he meets the fat man who was with him in South East Asia. "I'm going to hell," he says, shaking and petrified. "Don't say I'm crazy, because I know I'm not." Same fears, same paranoia, same demons. "What happened?" Jacob asks. "What happened that night?" He means in Vietnam, the night of the attack, the clue to the conspiracy, the heart of horror.

This is a fascinating film, not only for what it achieves, but for what it avoids. Psychological thrillers play tricks as entertainment. Often the trickery becomes the raison d'etre. Here, there are no tricks. Within the framework of an extraordinary story, which lays itself open to cinematic indulgence, the overriding factor is integrity.

The writer, Bruce Joel Rubin, made his reputation with Ghost, which grossed more than £500million worldwide. Jacob's Ladder won't match that success. It's too dark, fearful and terrifying, lacking the sentimental simplicity of a love-after-death tissue-tugger.

Nothing in British director Adrian Lyne's portfolio (Flashdance, Fatal Attraction, Indecent Proposal) compares to this. His use of New York, his careful control of horror techniques, his understanding of character and work with actors demonstrates qualities far greater than those of a man who once made commercials for a living.

It is as if everyone was waiting for this to test the limits of their talent. Robbins brings credibility to what appears incredible. Jacob has a mind of his own. His search for the key to alienation is an awsome journey into the unknown. He makes it feel like yours.

Reviewed on: 09 Mar 2003